- Home

- Zibby Owens

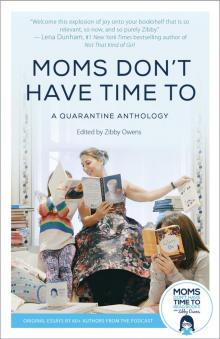

Moms Don't Have Time To Page 8

Moms Don't Have Time To Read online

Page 8

We started dating in February, and it didn’t take long for me to realize that he was an exercise guy. He had a gym membership and ran miles and miles in Central Park, even though it was cold outside. My own exercise consisted solely of walking to and from work. The walk took about half an hour each way, and it was one of my favorite parts of the day. I would pop in my earbuds and zone out, letting my mind wander, thinking about everything and nothing at all.

Winter became spring, and he tore a tendon in his ankle and had to undergo surgery. As soon as he was able, he was back in Central Park, first walking, and then back to running once again. He told me it was easier for him to think when he ran. I had since gotten a new job, one that required taking a forty-minute subway ride in each direction. I thought about my walks back and forth to work, and I wondered if running would feel like that—like my mind could get lost in itself.

I found that I loved not only running, but also racing. It gave my mind a chance to unfurl, and it felt good to push my body to become stronger and faster.

So, that fall, I told him I wanted to run, too, and asked if he would teach me how. On our first run together, he told me to go at whatever pace I wanted, and he would match it, and we’d see how long I could manage. We jogged together in the park, me breathing hard—him, not so much—for about fifteen minutes. At that point, we’d gone from West 72nd Street down the bottom loop and back up, almost to 72nd Street on the East Side. I told him I needed to stop, and he pointed to East 72nd Street, about half a block away.

“You can make it to there,” he said. “Then we’ll stop.”

I didn’t think I could, but I did. And then we walked home. That was lesson one.

We got into a groove on the weekends. We’d start out running together, I’d go as far as I could—and then a little more—and after that, I’d head home and he’d finish his run. He encouraged me to register for races, some of which we did together and some of which I did on my own, with him cheering me on. He taught me to push hard up a hill, to always run on the outside of the pack at the beginning of a race, and not to drink every cup of water that was offered. With his tips, I found that I loved not only running, but also racing. It gave my mind a chance to unfurl, and it felt good to push my body to become stronger and faster.

The following spring, I decided to train for a half marathon, and he helped me make a plan. I’d never felt stronger in my life. At the finish line, he seemed just as proud as I was.

But, like that race, our relationship finished, too. I lost him, but I didn’t lose running. One weekend, as I was running in the park, I saw someone wearing a triathlon shirt. I’m going to do that, I decided. I wasn’t a swimmer, and I hadn’t ridden a bike in a while, but I hadn’t been a runner either. I knew it would take time and work. But I had time and I wasn’t afraid of work.

I went online and found a sprint triathlon that was taking place at the end of July. That gave me sixteen weeks. I found a sixteen-week schedule I could follow, and then signed up. My first day in the pool was miserable. My first day on a bike was only marginally better. But I kept at it.

As the summer progressed, I visited my parents at their beach house, and my dad—a former collegiate athlete himself—decided he was going to be my coach. He stood at the ocean’s edge timing my laps in the buoyed-off area of the beach. I told him that time wasn’t important to me—I just wanted to reach the finish line.

The day of the race arrived, and I was ready. My parents came to cheer me on. When we got there, I found out that there was a serious undertow happening in the Atlantic Ocean. I didn’t let it worry me until I got in and realized how hard I had to tread water in order to keep myself from floating backward.

But like that race, our relationship finished, too. I lost him, but I didn’t lose running.

That swim was one of the most difficult things I have ever done—physically and emotionally. Halfway through, I thought I would have to give up; I wasn’t strong enough to overpower the undertow. But one of the lifeguards on a paddle-board told me to float for a while, and then get back to it. I thought of the way I would always push myself just a little further than I thought I could when I was learning to run. I flipped back over, and I swam.

The bike portion of the race came as a welcome relief after finally making it out of the water, and then, last was the run. I was pretty far toward the back of the pack when I started, but as soon as my sneakers hit the asphalt, I felt a surge of strength. My mind focused, and I felt the familiar rhythm of my footfalls. I pushed hard up the hill, and I crossed the finish line. I made it.

As I took a bottle of lemon-flavored sports drink from the table, I thought about how every experience we have shapes who we are. There’s no way I would have completed that race if my past had been any different. And in that moment, I was grateful. Grateful that a failed relationship had made me a runner.

Jill Santopolo is the internationally bestselling author of novels The Light We Lost and More Than Words.

These Days, I’m Running to Stay Sane

SARA SHEPARD

I put on shoes and slide headphones in my ears. If it’s cold, I add a hat, sometimes with a pompom on it, which bobs as I move, reminding me that it’s still there. My gloves are sometimes high-tech ones from New Balance but are just as often woolen mittens from Anthropologie or gloves so old the fingertips are fraying away.

I’m not the runner who’s in fashion or whose clothes even remotely match. I sweat a lot, and my skin gets unattractively red, and I’m not in neon-colored trendy sneakers but utilitarian black men’s shoes that are an update of an update of an update of a running shoe I was specifically measured for at a Super Runner’s Shop on 24th Street and 3rd Avenue in New York City in 1997. I have been wearing the same brand and make of sneakers, more or less, for twenty-three years.

That’s how long I’ve been a runner. Longer than that, actually. And every day, regardless of the weather, I go outside and do the same thing. I run the same neighborhoods, by the same houses. Often, I see the same people, or the same people see me.

“Oh, I saw you running,” they’ll tell me later. “You’re really dedicated. Are you training for something?”

No, I tell them. I’m almost never training for anything. For better or worse, this is just what I do.

When I was a kid, running was a means to flirt with boys on the junior high track team. In high school, it became an obsession and bridge to disordered eating. For a while, running was my favorite mode of punishment, a symptom of what I now understand was and is an illness. After moving to New York City, I slowly recovered. I regained a healthy balance. Since then, running has become a helpful aid in the writing process—I’ve been cracking big plot points mid-run for a good fifteen years now. The minutes of breathlessness serve as a time where I can work out complicated feelings.

While all those parts of my history with running are true, the sport has taken on a whole new meaning in the face of the coronavirus pandemic. Now, every time I step outside—and let me be clear, my running path keeps a safe distance from people—it isn’t just my workout for the day. It’s a valuable, life-saving routine. It’s a meditation. It’s an escape.

For a while, running was my favorite mode of punishment, a symptom of what I now understand was and is an illness.

This isn’t my first time running through big, scary moments in history. Post 9/11, I ran around Prospect Park in Brooklyn—the air still smelled like charred electronics and death—and tried to cope. When the banks crashed in 2008, I was living in Tucson, Arizona, and my house was abruptly valued at a hundred thousand dollars less than what I’d bought it at, and I ran on back trails amid rattlesnakes and coyotes and tried to figure out what to do. In 2012, I went through a difficult separation and divorce not long after having my first child, and I ran on a tranquil, wooded trail to try to dull my pain. Running has been a constant no matter what happened; often, when I return from a run, I feel better, more centered, calm.

And now,

in the face of COVID-19, it’s no different. On some of my latest runs, my mind keeps churning over the same brutal questions: When is this going to end? How can we stay safe? Is my career secure? What if my parents get this illness?

But there’s also one big difference between running amid those other crises and running through this one: I have children. Thinking, questioning, needy children—who, as it turns out, are now out of school for the rest of the year. So it’s not just my struggles I’m working out when I’m running these days—it’s also theirs.

Every person in the world shouldn’t be consumed with the same thoughts and worries all at the same time. It just doesn’t seem right, and yet here it is.

Like so many people, I’m trying to work from home with my kids now home as well. We’re limping along. At almost six and eight, they have somewhat of a grasp of what’s going on—though certainly not the unprecedented nature of it all—and at the moment, they’re chill about staying home from school. They’ve Skyped with friends and teachers. They’ve played outside. We’ve gone for (safe, socially distant) walks. But they’ve also watched a lot of YouTube, played tons of video games and Minecraft, and made ridiculous TikTok videos. On their first day off, I kept to a schedule of reading, math, science, and spelling. But as the week progressed and the news got grimmer and more real, that all went to hell. I wanted to say, oh it’s okay—it’s only been a week.

Now I’ve lost track of what week we’re on.

On my runs now, I’m not breaking any speed records or even pushing myself very hard. I’m barely listening to audiobooks (I keep having to rewind the thriller I’ve been listening to over and over because I can’t stay on top of the plot) and I’m shying away from every podcast in my feed, and I’m having trouble even brainstorming new books to write. Instead, I go out and run my miles and try as best I can to tamp down my anxiety. I think through worst-case scenarios. I make plans. I make lists. I allow myself to be distracted and scared and frazzled and irrational while I’m on the road, running alone, and after an hour passes, the feelings aren’t necessarily out of my system—they come back in the middle of the night, and keep me awake for hours. (Is anyone sleeping well amid this?) But that solid block of time of movement plus intense worry plus sweat plus the outdoors works. I come home a little more peaceful and centered.

Now, every time I step outside—and let me be clear, my running path keeps a safe distance from people—it isn’t just my workout for the day. It’s a valuable, life-saving routine. It’s a meditation. It’s an escape.

I am lucky. I know this. I am lucky because I have a good immune system, and because I have an emergency fund (though, like many others, it has dwindled), and because everyone I know at the moment is safe. I’m also lucky because I can still run—physically, yes, but also because my running path is appropriately socially distant. I feel for those living in New York or other busy cities where running while staying safe might not be as possible. I feel for people whose lifeline was, say, the elliptical machine at the gym and don’t have a comparable machine at home.

But mostly, I just feel for all of us right now. Whenever a person pops in my head—someone from my past, an ex-boyfriend, a random celebrity—I think, Good Lord, they’re dealing with this, too. It’s a bizarre feeling, and though it’s one of connectedness, it’s a connectedness of the worst kind. The whole world is suffering. For me, trying to conceptualize this is akin to staring into the sky at night and trying to grasp that the universe is infinite: it seems impossible. Every person in the world shouldn’t be consumed with the same thoughts and worries all at the same time. It just doesn’t seem right, and yet here it is.

So I’m going to say what a lot of people have already said, but bears repeating: get through this as best you can. Do what you need to do. If it’s that an extra glass of wine every night, go for it. If it’s eating extra carbs and watching terrible TV—thank God, there’s still TV—huzzah. And if you’re like me, maybe it’s lacing up your shoes and going for a run even though it’s pouring rain. We just have to get through this.

And we will.

Sara Shepard is the #1 bestselling author of the Pretty Little Liars series and many other books, including her most recent novel, Reputation.

What Locker-Room Talk Sounds Like to Me

BONNIE TSUI

When indoor pools closed, I missed my community in the changing room the most.

There are so many things to miss in this pandemic time. In summer—the season of the swimmer—family reunions, camps, and vacations are largely absent. The things we rely upon for mental and physical health are no longer readily available. Lately, I’ve been missing my community pool, where the locker room was a tableau on aging. There were bodies and bottoms of every sort on display, from squishy baby to saggy lady. But it was not the kind of place where short-lived resolutions to lose fifteen pounds got made or broken. The arc of fitness was long there, and it bent toward seniors.

Pre-pandemic, the hour in which I frequented the pool for my laps coincided with the 8 a.m. aqua aerobics class, taught by Kathe, a calm, convivial woman with honey-colored hair and a beatific smile. Many of her devotees ranged into their eighties. Some were there for physical therapy after an injury; others were contending with the incessant aches and pains of age. In that damp little maze of shared benches and open showers, where every flick of a towel or reach of an arm brought you into someone else’s personal space, ordinary civilities carried larger import.

I am not eighty. But among those eighty-year-olds is where I liked to be.

I am not eighty. But among those eighty-year-olds is where I liked to be.

I first came to this pool after my second child was born and my family moved across the bay from San Francisco to Berkeley. It’s where I reclaimed my body, a little softer and a lot more tired, as my own. Day after day in the outdoor pool, I pulled and kicked my way back into the swimming habits that made me feel like, well, me. More than five years later, my passage through each day was eased by the morning transit through this locker room, in the company of these women. The daily celebration of bodies that are happy and working made me comfortable and ever grateful in mine.

As a lifelong swimmer, I’ve found that my morning workouts smoothed away the edges, both strengthening and calming my restless body, so I could face the world with equanimity. But as I got older, I found that the locker room itself did something different for me.

It was where we warmed up from the swim in the communal showers; where we jockeyed for space in the crowded dressing area, all of us in various stages of nakedness: this one applying moisturizer, that one in underwear, still another wrestling with a stubborn pair of leggings. We contorted our bodies in the most unattractive ways. It was where we showed vulnerability, in all its forms, and felt safe doing it.

Loneliness, we know, deteriorates health. I listened to the way the people in this room rallied around each other—through struggles that ranged from family discord and sleeping woes to cancer and chemo and the death of dear friends. Sometimes I swam with a buddy, or trained with the Masters team. Often I came alone. But I always found company in the locker room—a conversation to dip into, or just to overhear. And there was always the comforting routine of simply discussing the water conditions in the pool that day, or admiring the pattern on someone else’s bathing suit.

I listened to the way the people in this room rallied around each other—through struggles that ranged from family discord and sleeping woes to cancer and chemo and the death of dear friends.

Certainly there were maternal and grand-maternal surrogates to be found there. Once, as we were getting dressed, I confessed to a friend that I didn’t know how to buy underwear anymore because all of it comes from my mother. She could eyeball the ideal fit of a bikini brief for me from a mile away and she refreshed my collection of undergarments every year in my Christmas stocking without fail. Another woman, perhaps a decade older than we were, listened to the story and got teary.

&nb

sp; “That is the sweetest thing I ever heard,” she said, wiping her eyes. “You should tell your mom I said so.” And so I did.

There was also wisdom and kinship on tap. Kathe dispensed nuggets about everything from mah-jong and yoga classes to the history of Title IX at nearby UC Berkeley, where she was once a student. Alicia showed Patricia her longtime stretching routine by getting right down atop her towel on the clammy tiled floor.

“I have been stretching all my life; I have scoliosis,” Alicia declared, mid-hip stretch. “If I didn’t do it, I’d be in a wheelchair now.”

Lovely Patricia with her British accent chirped anxiously above her, “I’m glad you’re not! But I think you’d better get up now dear, or you’ll get run over!”

As they sailed or shuffled or sauntered out of the locker room, the ladies called to everyone to have a lovely day. When they passed me at the long mirror by the door, they smiled and met my eyes, making me feel there was a solution for most every problem.

Locker room talk? This was our kind of locker room talk:

How are you?

I’m OK. I’m here, aren’t I?

The cackling laughter leaked out into the hallway. I could hear it all the way from the pool deck.

These days, three thousand miles away from a mother and grandmother and a gaggle of aunts I don’t know when I’ll see next, I think often of that laughter, and find a small measure of comfort in anticipating opening day at the pool.

Bonnie Tsui is a journalist and the author of Why We Swim.

Moms Don't Have Time To

Moms Don't Have Time To