- Home

- Zibby Owens

Moms Don't Have Time To Page 11

Moms Don't Have Time To Read online

Page 11

I did help her, however, deftly spinning dough circles with my married woman’s rolling pin. “These are so perfect,” my father-in-law remarked, “You could use a circle-drawing compass to trace them.” He meant to be generous and encouraging, and he truly was in every aspect of my life, but that sense that somehow I was being slipped something without my knowledge returned. There was something wrong with a picture where men sat at a table and offered not just praise but “constructive” criticism for meals they had no hand in making. It felt like a finely orchestrated farce perfected over centuries and generations.

Like so many immigrants before us, we turned to food as our glue. Feeding and being fed became synonymous with love.

My mother, a housewife who approached keeping house with the purpose of a CEO running a company, would tell you that this was her job: putting food on the table, spreading joy one taste bud at a time. She’d tell you that the praise was her certificate for excelling at a role she had chosen. I, however, had not chosen that job. I had a more advanced education and career than most of the men who sat there enjoying my rotis and not getting up to help.

Then I moved to the United States, a young immigrant. My husband and I got down to the business of building a life from nothing. Not just graduate degrees and new jobs, but creating community, making family from friendships. Like so many immigrants before us, we turned to food as our glue. Feeding and being fed became synonymous with love.

For the first few years I forgot my discomfort. I rolled dough and watched the perfect circles swell to spheres. Then it started; my ears began to pick out conversations that listed which wives in our circle made rotis and which did not. My ability to look away died a quick death as male friends tendered unsolicited roti-making advice without ever touching a rolling pin. I found myself again with that sense of being taken for a fool.

This sense grew like a slow flood going from connection to connection. All the ways in which I’d been shoved into roles, from being responsible for meals and my home to the care of everyone in my sphere to forcing my feet into heels that made my back hurt to shaving my legs and doing my hair. Things I might enjoy naturally, but I would never know for sure. It all became one.

I stopped making rotis—my very own grand declaration of independence. Fortunately for my husband, who is domestic in many ways but never once considered stepping into the roti-maker’s role, the Indian grocery stores in our town started stocking the blameless bread.

Then came the closed stores of this quarantine life, followed by the great bread-making wave. After nearly two decades, I finally broke. Turns out it’s like swimming. My body remembered the intricate strokes with the ease of someone indoctrinated young. With that memory returned all the reasons why I had stopped. But I also remembered how much I actually enjoyed it. Was that because there is something magical about turning out perfect bread, or was it because I knew I’d never go back to it as a daily chore? As is the case with anything we’ve been conditioned to believe about ourselves, I guess I’ll never know.

Sonali Dev is the author of multiple Bollywood-style love stories, including the recent Recipe for Persuasion.

In Provence, Soothed by Goat Yogurt

PHYLLIS GRANT

In the wee small hours, my mind goes to a supermarket in the South of France.

Advice: In the middle of the night, when your unregulated hormones jolt you awake, gently nudge the dog off your legs, flick the sweat off your chest, and consider mentally assembling galettes and salads. This survival technique might help you stave off the ever-present rabbit holes of distress about kids and remote schooling and COVID-19 and racial injustice that, in the deep dark night, feel vast enough to gobble you up. At 3:00 a.m., you will never ever have the answer to anything. So practice what you know.

Flash back to that hot Thursday last July in the South of France. While the rest of your family tours Marseille, cruising in a boat on the bumpy waves, heading toward the cliffs and caves of Les Calanques, you stand alone in the Monoprix grocery store in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, smiling broadly at the forty-foot span of refrigerator cases filled with French dairy. Nothing fancy or precious. Some local items. Some from up north. Some organic. Some not. Just magnificently abundant. You pile the grocery cart high with six-packs of fromage frais, mini glass jars of goat yogurt, pourable crème fraîche, tubs of fromage blanc, Beurre d’Isigny, and crème fleurette so thick you could cry.

You drive back to the empty house, stand underneath the wisteria, and let the yellow jackets encircle you. The noon heat forces you to sit down and drink crisp, cold rosé. The rules feel different.

Moving quickly, you roll your tart dough out into a jagged circle, giddy as the neon-yellow butter spreads like a spider’s web. For the base, you whip together goat yogurt, crème fraîche, crème fleurette, egg, lemon zest, and salt and spread it out evenly over the dough with a butter knife.

At 3:00 a.m., you will never ever have the answer to anything.

Then add some slow-cooked tomatoes from the previous day’s lunch. Some chopped herbs. Blobs of ricotta because: why not? A clockwise folding in of the edges. Egg wash. Extra salt. A quick fix to prevent a leak. And into the oven. The kitchen appliances are unfamiliar so you stick around and peek through the oven window as the tomatoes and whipped dairy bubble and brown and rise and then fall from the bursts of high heat.

While the galette cools, you tuck peach and avocado halves together on a large dinner plate, filling all of their bellies with garlic oil, pickled onions, and Champagne vinegar. Then a bit of parsley and coarse salt. A thwack of lemon zest. And then splat. Splat. Splat. Crème fraîche everywhere.

If you aren’t asleep by now, just get up and start cooking.

Crème Fraîche

I splash this over pasta, stews, avocado toasts, and tacos. I mix it into green goddess dressing, tart bases, and pesto. It is a wonderful replacement for sour cream. It’s a lovely way to cut the sweet intensity of a cake or pie. Once you have it in your life, you will be tempted to use it every single day.

1 cup heavy cream

2 tablespoons buttermilk

You roll your tart dough into a jagged circle, giddy as the neon-yellow butter spreads like a spider’s web.

Pour the heavy cream and the buttermilk into a jar with an available lid. Stir just to mix. Put on the lid. Leave it on the counter. The thickening and souring take anywhere from 1 to 4 days. The hotter your kitchen, the faster it will go. Stir and taste every 12 hours or so. Once it’s to your liking, store it covered in the fridge for up to a month. I make this every two weeks. Every six months or so, a batch doesn’t work. If it smells or tastes like blue cheese, toss it and start over.

Recipe from Everything is Under Control: A Memoir With Recipes by Phyllis Grant1

Phyllis Grant is a three-time Saveur Food Blog Award finalist for her blog, Dash and Bella. Her latest book is Everything Is Under Control: A Memoir with Recipes.

1 Reprinted with permission from Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

What I Saw at Your Kid’s Birthday Party

LAURA HANKIN

Confessions of a children’s musician for the one percent.

I used to sing at children’s birthday parties. As an aspiring writer and performer, I needed a flexible day job. And after a series of false starts as a flash mob coordinator (yes, that was a real thing) and an assistant to a psychoanalyst who needed therapy of his own, I discovered the lucrative world of kids’ entertainment.

On any given weekend, I lugged my guitar and a bag of egg shakers across New York City like a wandering minstrel, entertaining wealthy babies in their gorgeous apartments. After I finished singing, the mothers would often invite me to stick around for a plate of party food. It might have been more dignified to graciously decline and get the hell out, but here’s the thing about me: I am incapable of turning down free food.

So I’d load up a plate of hors d’oeuvres—deviled eggs, toothpicks of caprese. Sometimes, the parents had gone for full-on catered meals,

and I’d ladle spoonfuls of chana masala onto my plate, or cut a piece of rich, steaming lasagna. And always, there was cake: flourless chocolate tortes from fancy bakeries or ultra-sweet concoctions with the Paw Patrol pups drawn on top in unnaturally bright icing.

The free food created a problem, though. While I ate it, I had to stay and hang out. The parents had hired me to entertain, and I had served my purpose. Now who was I supposed to talk to? Should I continue to play with the children even though I was off the clock? Or did I dare talk to the adults? I felt as awkward as a middle schooler, scanning the cafeteria for a table where I belonged. Generally, I just gobbled my food as quickly as I could, and watched the party play out.

In the noisy, sticky crowd, the mothers whirled, holding a champagne glass in one hand and wiping the crumbs off their child’s face with the other. The celebrations they threw for their children were often lavish, packed with eighty of their closest friends like miniature weddings. Sometimes, in the midst of playing perfect hostess, their frustration came through, frustration with partners who weren’t helping enough, or with children who wouldn’t let them finish their conversations.

On any given weekend, I lugged my guitar and a bag of egg shakers across New York City like a wandering minstrel, entertaining wealthy babies in their gorgeous apartments.

I wondered, as I devoured my Brie and crackers, if my life would ever look like theirs. If someday I would have a husband and we’d put on our finest clothes to celebrate our one-year-old. I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to afford to have children on an artist’s salary. And maybe I didn’t want them anyway—how would they affect all the big dreams I had for my career? Sure, at the moment I was spending more time traipsing around to these birthday parties than being creative, often too exhausted by the time I got back home to do much more than collapse in front of the TV, but still. I felt that if I were to have children, I would need to establish myself first so that people would miss me when I took time away and be willing to accommodate me when I came back. And yet the years were floating by and I seemed to be getting no closer to establishing anything at all.

I was in my mid-twenties when I started doing these parties, but as my thirtieth birthday drew closer, the mothers started to look different to me. Sometimes they still grimaced in frustration. And sometimes they laughed with pure delight, so lucky and happy to be exactly where they were.

I was in my mid-twenties when I started doing these parties, but as my thirtieth birthday drew closer, the mothers started to look different to me.

As I shoveled down some chicken fingers at an “On the Farm”-themed birthday party that would turn out to be one of my last, I finally realized I couldn’t do this forever. I wanted a life where I was building something. I didn’t need to throw the event of the season for my one-year-old. But maybe I did want, someday, to be the mother offering a plate. Maybe I wanted to shovel down food not because I didn’t know what to do with myself, but because I had so much to do and needed to get back to it.

I finished the cold chicken tender and wiped my fingers on a balloon-patterned napkin. I waved goodbye to the busy, whirling woman who had hired me. “Thank you!” she called out. Then she returned to her life and I walked out the door.

Laura Hankin is a performer and author of the debut novel Happy and You Know It.

To Papayas, With Love

COURTNEY MAUM

Quelling my pandemic fears in Mexico, one fruit at a time.

I stood at the bottom of the cobbled driveway contemplating the desiccated orange halves and yellowed husks of corn below the thorn trees and I knew that my life was about to change, in a big way.

No more Western Mexico. No more scorpions hiding behind my daughter’s pillow. No more hauling compost a quarter mile through the jungle so the coatis didn’t rip through the kitchen window screens to get at our garbage. With the exception of the scorpions, these realizations brought me sadness, not relief.

I was in my sixth week in Careyes, a small coastal community in the rural state of Jalisco on Mexico’s Pacific Coast. I’d come to Mexico on March 8 with my husband and young daughter to promote the Spanish edition of my latest novel, Costalegre, and then COVID-19 hit—or rather, COVID-19 escalated—to a degree that presented an urgent question: should we stay or should we go?

There were tons of considerations on the “stay” side and only two on the “go” end: “Wi-Fi” and “our cat.” But our cat was safe in Connecticut with friends who were happy to have him. As for the Wi-Fi, the Internet was zipping panic through a billion routers, so that left zero reasons to leave the place we were.

In Mexico, I developed an orange juice addiction that felt like the start of an affair.

A free home in paradise, infinity pool privileges, all of these were no-brainer reasons to stay put, but one of the more serious ones was access to fresh food. In the pictures my phone brought me (dispatches I accessed by hanging over a banister situated on a cliff to get one bar of network) I saw supermarkets emptied of toilet paper, body soap, poultry and meat products, all produce gone but durian, nowhere to buy flour. I live in a rural part of the Northeast where the closest grocery store is a struggling Stop & Shop. Stadium-sized, glacially air-conditioned, and staffed almost entirely with self-checkout terminals, it is a shopping experience so depressing that I listen to a sex podcast when I go there to distract myself from the fact that even the ripest vegetables look like they came to our grocery store to die.

As a self-employed writer married to an independent film director, we survive the ups and downs of a creative life by spending carefully, but in our corner of northwestern Connecticut, even a rote trip to the grocery store ends in a three digit receipt. From a culinary perspective, returning during COVID-19 would mean spending money we weren’t earning on food we didn’t enjoy. Though I don’t consider myself a foodie, I do think of food and beverage as a great reward system: you nail your presentation, there’s a plate of carbonara pasta waiting on the other side. This habit of equating food with gratification is problematic, childish. It’s one of the reasons I didn’t feel up to the task of homeschooling my daughter for the payoff of frozen cauliflower florets.

So we stayed in Mexico. We stayed among the papayas that ripened on slim trunks, the limes greening on branches, the mangos weighing down the broad leaves of the trees that dutifully bore them. Although we didn’t have an oven, a short car ride took us to a corner store where a husband and wife team pressed out fresh tortilla rounds, the heat of the wax-paper package a replacement for another human’s hand. In Mexico, I developed an orange juice addiction that felt like the start of an affair. Unsustainable and tenuous though this new love was, I nonetheless kept at it: four oranges squeezed into an elixir of optimism and hope each morning, a dose of vitamins that built a wall against my dread.

When another day came to a close without a family breakdown, we barbecued pineapple with a pinch of lime.

We were tasked with jobs in our tropical shelter: my daughter spotted scorpions and my husband caught them (it pains me to say “killed” although that was the end goal), and I cooked and walked the compost into the jungle every day. This chore was performed in the grueling heat of day’s end or the mosquito rave of nightfall, and while my epidermis didn’t win in either scenario, I came to love the daily descents that gave me the opportunity to appreciate the food that nourished my family and eased my anxious mind. My latest book tour was canceled, all my speaking engagements, nixed. Deals that would have brought me income had vanished into thin air. When these realizations edged at me, an avocado doused in sea salt and olive oil was a balm to my new fears. When another day came to a close without a family breakdown, we barbecued pineapple with a pinch of lime. When the sun came up and it was time for us to be on top of one other once again, cuts of ripe papaya gave us fortitude—and fiber—for the day ahead.

And so it was that my compost duties became a cherished ritual; the dumping of egg shells, candles to an altar. The scattered orange halves

, the wrinkled limes, the slicks of papaya wet as dolphin’s skin, with every remnant that tumbled out of the plastic compost bowl that I carried, I gave thanks for the pause button that Mexico had given us; the incredible opportunity to take time, reflect, reset.

Eventually, however, the abundance of fresh produce could not make up for the lack of Internet in our jungle house. With nowhere to purchase books and mail delivery impossible, we’d run out of materials and activities to homeschool our daughter with, and I couldn’t teach any of the online classes that were keeping my fellow writers sane. Our decision to leave was made easier by the fact that our hostess had found someone who wanted to rent her entire place as a “pandemic escape” for two thousand dollars a night.

We purchased a homeward ticket for the fourth of May and we got on a plane, and then we got on another plane, and both planes arrived where they were supposed to, at the time that they were supposed to, with 15 percent of their seats filled. There wasn’t any food or beverage service in-flight, but we were handed a gift bag containing a single bottle of water by hands wrapped in plastic gloves. In the checked baggage below us, we carried clothes worn by two months of dust and sunshine alongside a six-pack of toilet paper that we’d bought before the flight.

It was time to face our new reality. The home we would return to had been irrevocably changed. I had no idea what lay in store for me or for my family when we got off the plane. I didn’t know what items would be left in the picked-over aisles at Stop & Shop. But I knew that we had been tremendously fortunate to enjoy the gift of isolation in a place where fruit fell from the trees only to split open and create new trees again.

Courtney Maum is the author of multiple books, including the novels Touch and Costalegre, and the nonfiction guide Before and After the Book Deal.

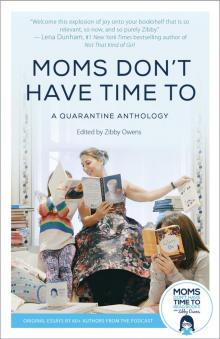

Moms Don't Have Time To

Moms Don't Have Time To